Does a piece of art ever burrow into you and swallow you up from the inside out? Bill Condon’s Kiss of the Spider Woman is the latest iteration of the story’s history of adaptations, from the original book to a film and musical. This film has been unwilling to leave my consciousness, popping up at random moments in my head. (Major spoilers ahead.)

The film is set in 1983 Argentina at the tail end of its Dirty War, an era of state terrorism where an estimated 30,000 people were disappeared or murdered by the government. Molina (Tonatiuh), a queer window dresser serving an eight-year sentence for public indecency, is assigned to a cell with Valentín (Diego Luna), a political prisoner and Marxist revolutionary. Later, it is revealed Molina’s placement is a manipulation by the warden to try and gain information from Valentín.

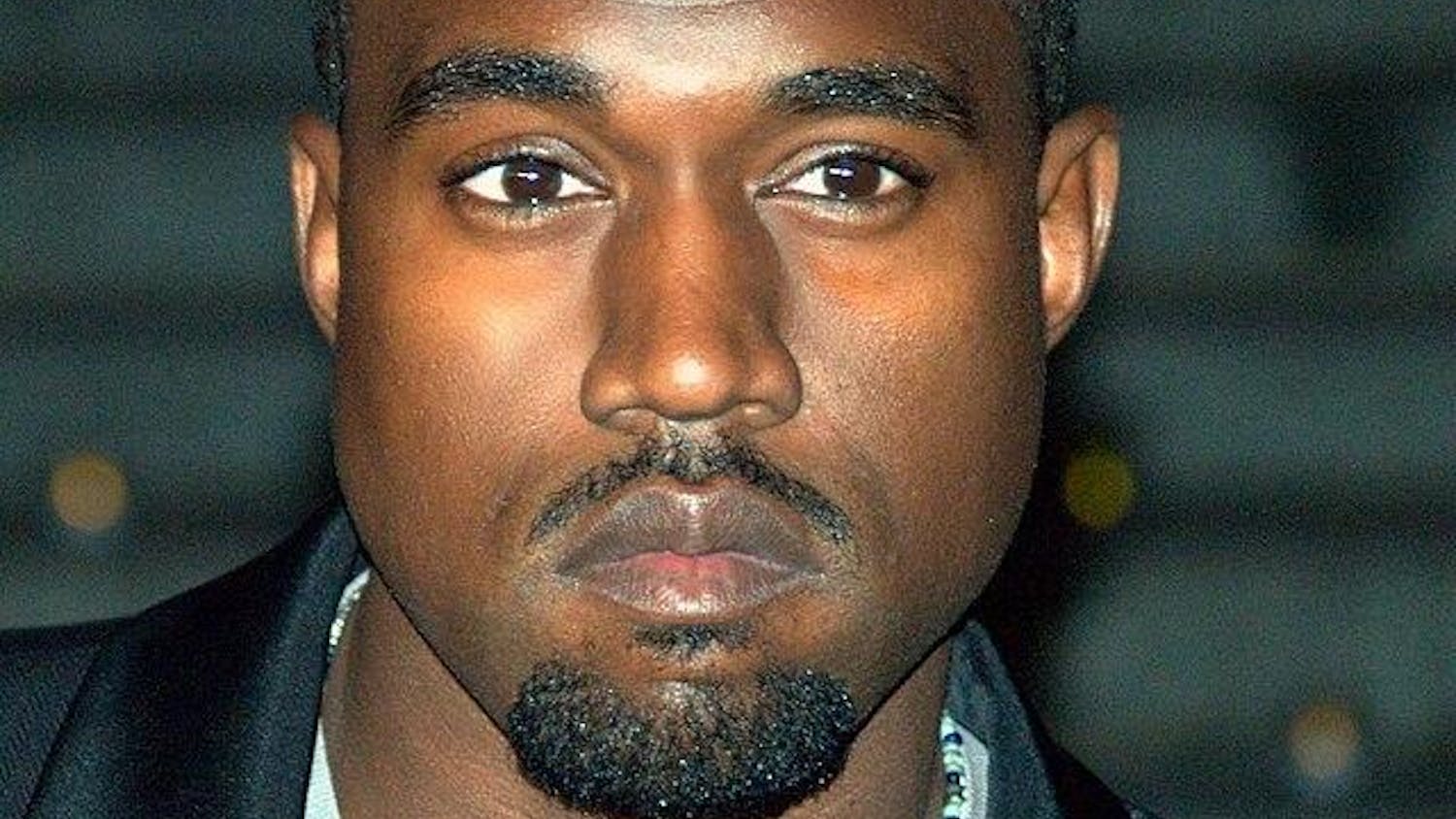

Molina’s flamboyant and staunchly apolitical personality clashes with Valentín’s serious demeanor. But to escape the reality that they’re in, Molina tells Valentín the plot of their favorite movie, Kiss of the Spider Woman, starring their favorite actress Ingrid Luna (Jennifer Lopez), who plays two characters: Aurora, a magazine publisher and diva, and the mysterious spider woman.

The movie-within-a-movie’s scenes are so full of color and life. At the point when we first switch into the musical, the saturated colors burst across the screen with such vividity I could almost physically feel the visual shift. Jennifer Lopez is a force in her scenes, and her solo/center dance performances are simply stunning, particularly the “Where You Are” and “Gimme Love” sequences.

As we flit between the bleak and brutal reality of the prison and Molina’s Technicolor fantasy, art and life blur together. In his retelling, Molina casts Valentín as Armando, the love interest, and themself as Kendall Nesbit, Aurora’s closeted personal assistant. The film transforms both Molina and Valentín as it entrenches them in the other’s lives. It brings them closer together, fostering both escapism and comfort.

It is hard to not also identify Molina with Aurora. Molina and Valentín grow closer alongside Molina’s idolization of Aurora and the Armando-Aurora romance, further placing the two storylines in parallel. In “She’s a Woman,” Molina-as-Nesbit yearns to be able to do feminine coded actions like wear makeup and perfume the way Aurora does. Molina lives vicariously through Aurora and the fully realized femininity she embodies.

The spider woman in particular fascinates me. She is associated with a curse on Armando’s village that requires the sacrifice of a man, which threatens the relationship between Aurora and Armando. When Nesbit ultimately sacrifices himself to let Aurora and Armando have happiness, Molina describes the spider woman as having “saved a whole village and asked for so little in return.”

I read the spider woman as a manifestation of the full realization of the self, in part alluding to Molina’s journey of (semi) radicalization. In Molina’s dying moments, after they are released from prison and shot while passing on information to the movement from Valentín, we are again transported to the fantastical realm of the spider woman. In direct parallel to a scene centering Aurora earlier in the film (“Her name is Aurora”), Molina takes center stage, debuting in lipstick and perfume and a skirt. “Her name was Molina,” the chorus sings. The stage lights go out on Molina kissing the spider woman. In the film-within-the-film, kissing the spider woman is synonymous with death. Yet, with the dynamic of Molina being haunted by the spider woman and her characterization as a hero, the spider woman also reads like the self waiting to be realized. Death, positioned with the flourishing of gender experimentation, can be read as new life.

The film is a testament to how art can be and is a mode of survival, and also how art is a call to action and a fuel for mobilization. The medium of film in this case is everything to Molina. It is an escape from reality that allows for survival, a sandbox for them to explore themself and in the words of Diego Luna, “a mirror that helps you transit reality.”

The beating heart that drives the film for me is the relationship between Molina and Valentín. The romantic element is there long before it is acknowledged by the characters, with just how deeply the two care for each other overflowing in their behavior. Valentín’s confession bubbles up as a tragic “my love” towards the end of the film, tender and heartbreaking at the same time.

"They [Molina and Valentín] rip joy and beauty from the most darkest of places," Tonatiuh told NBC News. This connection — created defiantly in the worst of possible spaces — allows for survival. Their relationship demonstrates the transformative power of love and connection. Molina and Valentín care so deeply for each other by the end and it changes each person from the inside out.

Speaking about the film to Entertainment Weekly, Diego Luna said, "When there's no chance to love, there's no chance to change. Therefore, there's no chance for revolution to happen or exist. These characters are really hoping change comes, but they have to go through their own process to learn that change is actually possible."

I love this unapologetically queer and anti-fascist film that reminds me how important art and love are to being human. The art-love as survival rings so deeply to my core. Walking out of the theater in a daze and now writing this days later, I feel like this film crawled into my chest and my brain and demanded I be filled with love for art and stories like this. It is a warmth against my heart, and I think I have become more whole as a human because of it.

Pen Fang is a sophomore in the College of Arts & Sciences. They can be reached at pfang@cornellsun.com.