It is written that, at the festival of Lupercalia, the consul Mark Antony offered Julius Caesar a laurel-wreathed diadem. The gesture was met with slow, scattered applause. But when Caesar brushed the crown aside, the crowd erupted in cheers. Antony brought it forward again, and when Caesar refused it once more, the forum roared with greater acclamation.

The irony is that, even as Caesar refused the crown, he did so from a golden throne, dressed in a triumphal robe.

Staged or not, the event was intrinsically performative; at the time, Caesar was a king in all but name. Just days earlier, he had proclaimed himself dictator perpetuo —dictator for life — an office he’d be the first and last to assume. The position of dictator then carried different implications. It was a post only meant to be taken for the duration of great crises, like war or civil discord. Nonetheless, the strength of the republic was crumbling under the grip of his autocratic rule, and Caesar knew well that the Senate was sharpening its knives. His assassination less than a month later says as much.

Nations rise and fall, though it is the very design of democracy, the meticulous balance of the government and governed, that makes such a system vulnerable. Caesar’s death provided an open throne, which his adopted son Octavian was more than happy to seize by force, marking the beginning of the empire.

The late Roman Republic is a textbook example of democratic backsliding. Severe factionalism split the Senate into two: the Optimates, who championed the aristocracy, and the Populares, who lobbied for the common people. It’s the Roman equivalent of political polarization, which has only intensified in recent years. Although democracy has its origins in polarization, it’s only when bridges burn, when entire groups and ideologies are demonized, that democracy begins to erode. More often than not, it results in major actors violating the rules of the game in order to advance their political agendas and repress oppositional forces.

Such a process is promulgated by the rise of an autocratic leader within a mainstream party, like Caesar. The reason why the republic so easily transformed to empire when falling into the wrong hands was due to Caesar’s blatant disregard for the democratic norms that consuls held themselves to in the past. The byproduct of this executive aggrandizement? By the time of his death, he’d turned the seat of dictator into a throne fit for an emperor, figuratively and literally. Whoever took the seat after him, whether it be Octavian or Mark Antony, was fated to enjoy imperial powers.

It’s not too hard to draw similarities between the republic’s final months and the current state of American democracy. Since the first Trump era, the American government has drawn closer to the makings of an electoral autocracy. Electoral autocracy is a hybrid regime in which elections are competitive, yet they are held on an uneven playing field, and there exist restrictions on the imperatives of a free society, such as the press, state resources, non-governmental agencies and dissenting forces.

Jan. 6, 2021 was Trump’s very own coup d’etat, a most apparent example of democratic erosion, though Trump has made more than enough efforts since to expand his executive power and undermine the other branches, which is especially easy due to his “trifecta” control of government power. He’s even discussed, on multiple occasions, the prospect of a third term, a most telling sign of his future plans for American democracy.

Democracies can be easily subverted through democratic means. For one, Trump’s tariffs are justified through the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, which gives the executive branch power to control some aspects of economic policy in times of national emergency. Normally, these tariffs would have to have originated in Congress, which is the governmental branch which holds the power of levying taxes, but Trump has claimed this state of emergency in order to expand his power.

Furthermore, Trump has made consistent efforts to limit voter access, most notably on March 25 when he bypassed Congressional approval and signed an executive order that would require Americans to provide proof of citizenship with a voter registration application. This would block tens of millions of citizens from voting, as it would require for most to bring a passport, which is not held by 146 million Americans. This, combined with the fact that around 40 percent of active registered voters register for the first time or update their voter registration every federal election cycle, demonstrate how big an impact this executive order would have if enforced.

Most relevant is his crackdown on intellectualism. Trump has threatened to cut, and in some cases has already frozen hundreds of millions of dollars in funding towards universities in an effort to get higher-education institutions to comply with his demands, specifically banning diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and deporting international students for their activism.

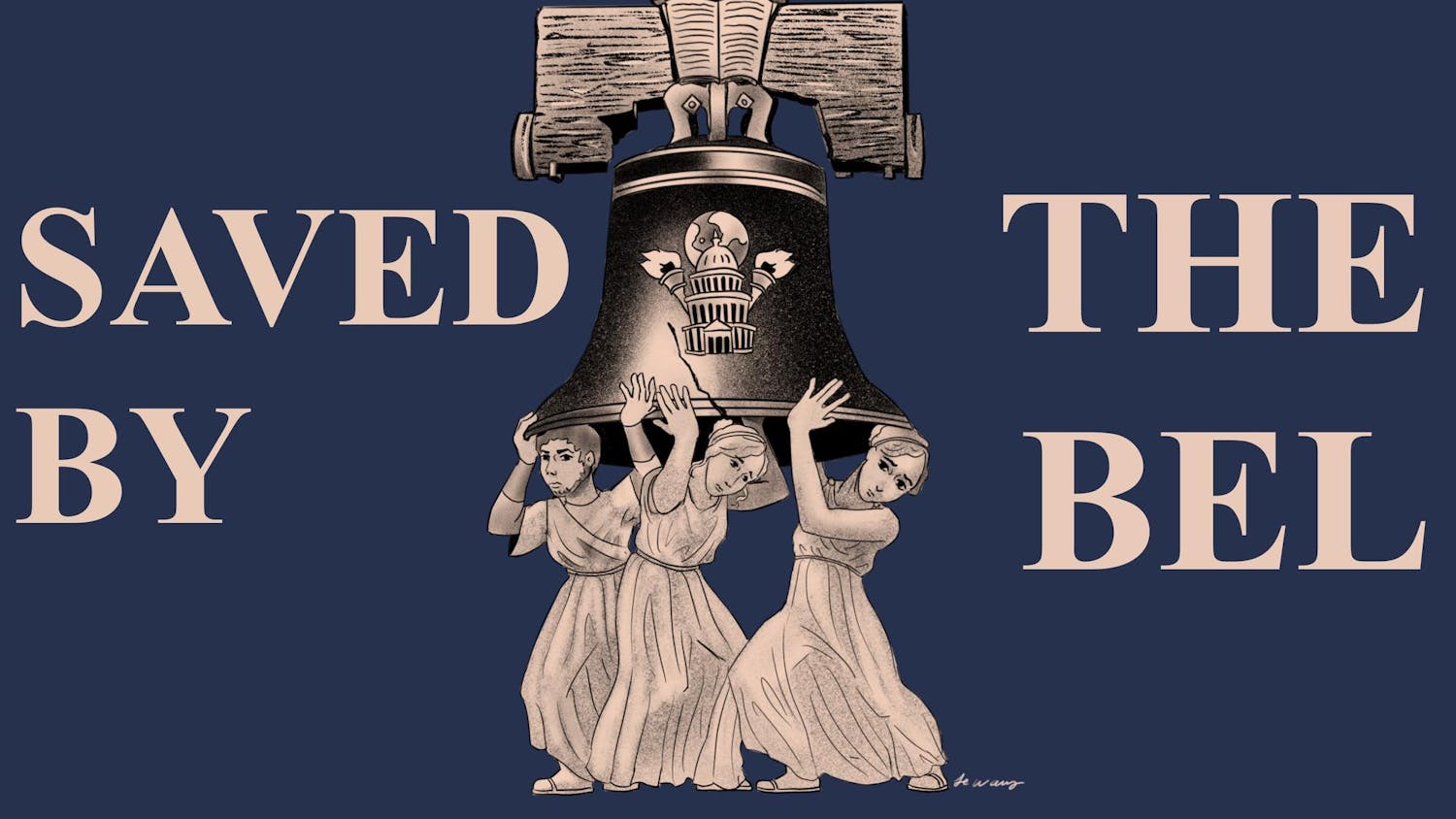

Through these efforts, Trump has not only reshaped America in his vision, but also somewhat transformed the presidential seat into a throne, a throne not so far off from the one that Caesar sat. But the throne is flimsy, and just as democracies crumble, a hybrid regime can be reformed at the same time.

Reader, I implore you — Watch the throne. In the end, it is not the face, the figure behind the power that leads nations into authoritarianism, but it is the stretching of precedent, the disregard of the norms essential for democracy, that brings us closer to Caesar’s throne with each passing day. Even when Trump loses power, the precedent will already be set, and our democracy is vulnerable to whichever politician tries to fill the throne.

Sic semper tyrannis – Thus always to tyrants.

The Cornell Daily Sun is interested in publishing a broad and diverse set of content from the Cornell and greater Ithaca area community. We want to hear what you have to say about this topic or any of our pieces. Here are some guidelines on how to submit. Feel free to email us: associate-editor@cornellsun.com.

Leah Badawi '27 is an Opinion Columnist and a Government and English student in the College of Arts & Sciences. She also serves as the Co-Editor-in-Chief of Rainy Day Literary Magazine. Her fortnightly column “Leah Down The Law” reflects on politics, history, and broader culture in an attempt to tell stories that are often left between the lines. She can be reached at lbadawi@cornellsun.com.