Picture this: it’s a cold February day in Ithaca, and you’re sitting in a cafe sipping a steaming drink over your homework. By chance, you look up from your problem set and meet the gaze of a cute stranger across the room. Your heart starts beating fast and you experience that all-too-familiar feeling of butterflies in your stomach.

As you debate whether to approach this person, your nucleus accumbens — commonly known as the brain’s “reward center” — starts releasing dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with pleasurable experiences like getting a good grade or eating delicious food, according to Prof. Alex Ophir, psychology.

At the same time, the hormones oxytocin — often dubbed “the love hormone” — and vasopressin work to make certain stimuli more rewarding to your brain; namely, the person who’s caught your eye. This creates an initial association between feeling good and a certain individual’s unique characteristics, according to Ophir. This subconscious motivation to seek higher reward helps you work up the courage to finally get up and go over to them.

Ophir studies pair bonding in prairie voles, a small rodent that is known for its monogamous lifestyle. In prairie voles, initial pair bonds are formed when oxytocin and vasopressin assign higher reward to certain individuals and human mechanisms are extremely similar.

However, there are key differences among individuals when it comes to the neurobiology of attraction. Prof. Nora Prior, psychology, studies monogamous pair bonding and friendship in zebra finches. Her research has found that long-term monogamous pair bonds and friendship have overlapping impacts on many brain networks, including the nucleus accumbens.

“While people often talk about key changes in hormones like oxytocin — the love hormone — and vasopressin there are also lots of changes in other neuromodulatory systems,” Prior said. “The neurobiology of falling in love and staying in love is quite complex, and is likely a bit different for each of us.”

With that in mind, let’s get back to our scenario. After striking up a conversation with this cute stranger, you find that the two of you actually have a lot in common. As you continue to chat, you find them even more attractive.

This is an example of what psychologists call synchrony — shared interests with another individual that increase the level of excitement and reward in your brain. Synchrony, paired with intellectual stimulation as you chat with your newfound crush, can create and reinforce the initial “spark” of attraction.

Although the initial spark you experienced was primarily based on physical perception, this deeper attraction, reinforced by further reward, is a result of social learning that you’ve experienced throughout your lifetime, shaping your preferences and opinions.

For this reason, we may not know as much about our own romantic preferences as we might think. “Even though individuals may be drawn to a certain type of person, they are not always consciously aware of what attracts them,” said Prof. Vivian Zayas, psychology, whose research focuses on the cognitive aspects of love and attraction. “Interestingly, the traits people claim to desire in a partner do not always align with the characteristics of those they actually find appealing in real-life interactions.”

After your conversation ends, your crush expresses interest in a date, to your utmost delight. A few days later, you’re on your way to your first date with them at a nice restaurant. Make sure to keep an eye out for some key biological markers of success, including excitement, positive anxiety and synchrony.

“I think that there's an important level of synchrony, and what I'll describe as ‘groove,’” Ophir said. “Are you in the same groove? Are you in sync? Are you out of sync? If that's going well, and it's paired with a positive, rewarding experience with some of that arousal and positive anxiety, then that's the signs of a good date.”

Through some stroke of luck, you make it through your date, and even though you were totally nervous, you also thoroughly enjoyed it. Several dates later, you and your crush decide to enter a long-term relationship.

The formation of a long-term pair bond in prairie voles is a catalyst for a shift in the brain’s dopamine receptors. According to Ophir’s research, after falling in love, a different receptor begins to dominate in the prairie vole brain, making it harder to feel attraction to individuals other than one’s own partner. Some evidence suggests that human brains work similarly.

That’s not the only change that happens in your brain chemistry throughout a romantic relationship, though. Many relationships begin with a stage of passionate dating before transitioning into a trust-based love that resembles a deep friendship.

“That social, selective social attachment that you see in the first early stages changes over a longer period of time when you push it out,” Ophir said. “Life basically gets in the way.” However, long-term studies on love across a human lifespan are limited, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

This doesn’t mean being in a long-term relationship can’t be rewarding. According to Zayas, “The rewarding nature of relationships extends beyond pleasure. It has motivational and cognitive implications as well. We seek proximity to loved ones, frequently think about them and engage in behaviors that help maintain these relationships — even when faced with the common challenges of relationships.”

One such reward involves the simple act of thinking about loved ones, which can be beneficial to brain health. “Loved ones often occupy our thoughts, and simple reminders of them can evoke positive emotions,” Zayas said. “This can lead to various benefits, including emotional resilience, a sense of calm, and an openness to new experiences, such as trying a new activity.”

Another critical topic in the science of long-term attraction is, of course, infidelity. In his recent research, Ophir explores why people — or prairie voles — cheat on their partners, even if they know it’s wrong and even if they claim to still be in love with their partner.

The answer, according to Ophir, lies in a combination of strong motivation and opportunity. In prairie voles, cheating may drive greater reproductive success because it allows them to mate within their pair bond and outside of it, providing valid motivation for cheating — at least on the evolutionary front.

Ophir also found that the probability of a vole leaving its nest is proportional to the chances of it being cheated on. He believes that infidelity is a consequence of how social an individual is, because being in social settings inevitably increases opportunities to cheat. “Maybe the lesson is: go on a date, stay together and stay home,” Ophir said.

Don’t lose hope, though, even if you find yourself struggling to navigate the treacherous waters of modern relationships, situationships or anything in between. Those not-so-comforting words your friends say to help you through heartbreak — “You’ll find someone else” or, if they’re feeling metaphorical, “There are plenty of fish in the sea” — actually have some scientific basis.

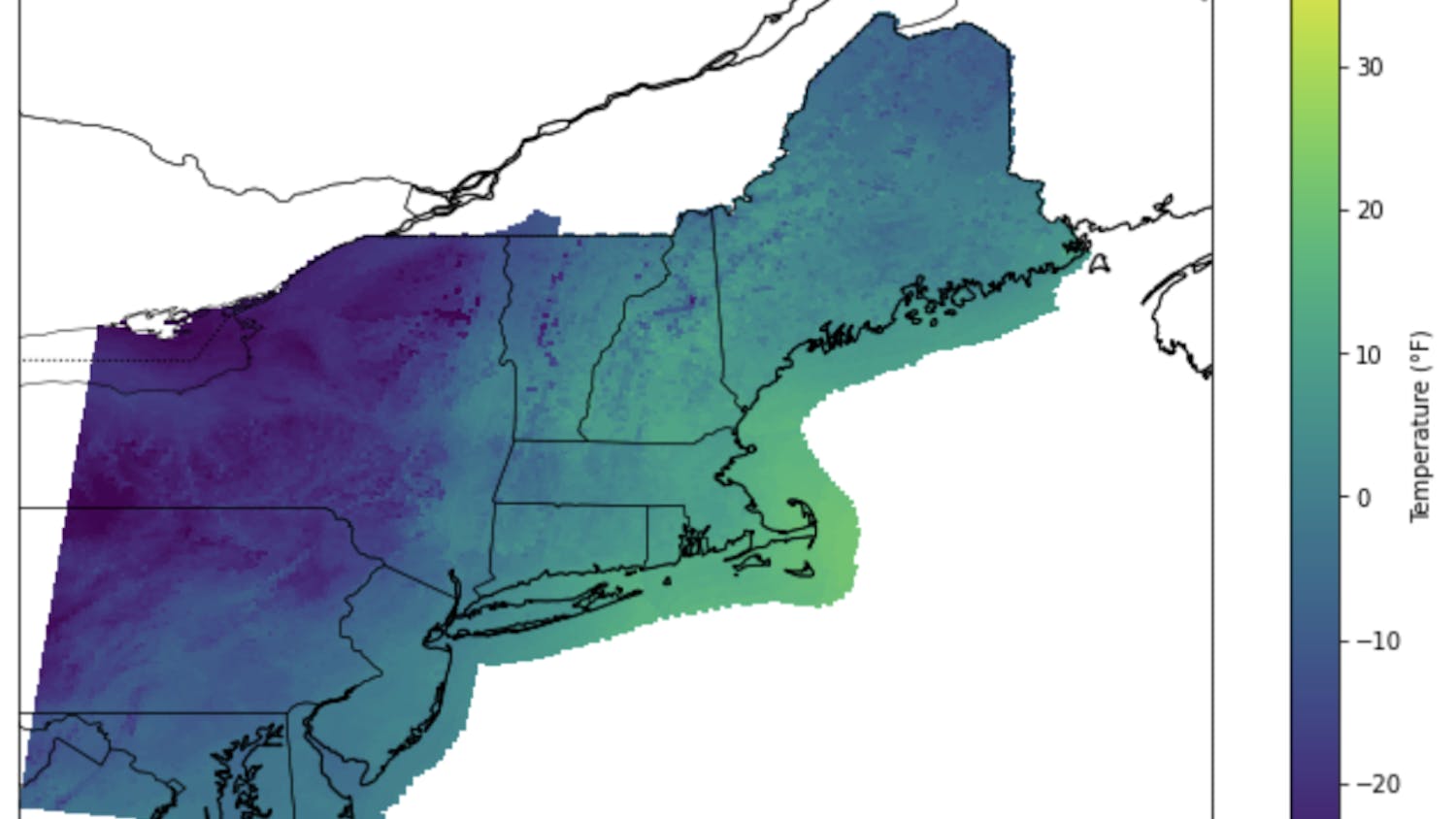

It turns out that a lot of attraction happens completely by chance. The neural circuitry involved with the initial spark of attraction to another individual depends on a wide variety of factors, including outside the time of day, day length, temperature, your body state and — perhaps most importantly — your mood.

“Really, it's just finding the right match, at the right time, in the right context,” Ophir said. “I think there are many ‘the ones’ for any person. And I think ‘the one’ depends on what time it is.”

Tania Hao can be reached at th696@cornell.edu.